Raw Rights

Local goat farm takes a stand

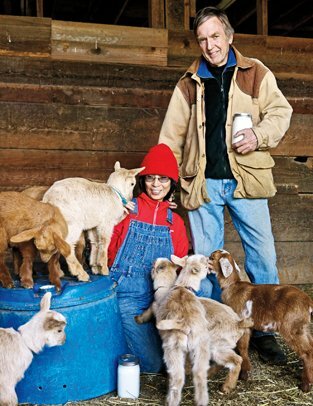

Mike and Jane Hulme with the kids of Evergreen Acres goat farm at their new location in Hollister.

Photographs by Lane Johnson

Five families in San Francisco used to take turns picking up the group’s fresh goat milk shares each week. They were among the approximately 300 Bay Area residents who had a private contract with Evergreen Acres, a goat farm located in San Jose until March 2012, and now moved to Hollister.

These families signed a herd-share agreement, in which they pay a farmer to board, care for, and milk their “share” of a goat. In return, they are provided with milk. Farm owner Mike Hulme, a former engineer and physicist, says, “I’ve been on this farm for over 20 years. We started the dairy about six years ago.”

High in vitamins, minerals, enzymes, and bioactive compounds, raw goat milk is touted for its myriad health benefits. Acceptable to most lactose-intolerant individuals, goat milk’s smaller protein and fat molecules and essential fatty acids make it easier to digest than cow’s milk. Preserving the quality of the milk by consuming it raw, instead of pasteurized, is the key for many consumers.

“Pasteurization practically cooks the milk, making it indigestible and toxic to your system,” Hulme says.

Before receiving a cease-and-desist letter from the Santa Clara County District Attorney's office and the California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA) in May 2011, Evergreen Acres Farm bred and sold goats and provided the Bay Area with raw herd-share goat milk.

Evergreen Acres’ goats were milked twice a day and the milk was put into sterilized containers before being refrigerated and delivered to shareholders, or picked up by customers who came to the farm with a sterilized jar from home.

“It’s very simple and very clean,” Hulme says of the process, which is now deemed illegal. According to current law, individuals are permitted to milk their animal at a herd-share farm, but they must consume the milk on-site. If the milk is moved from the farm, the farm is classified as a “distributing dairy” and is held to current certification laws. For Hulme to comply and become a certified dairy, he would have to install more than $100,000 worth of buildings and systems, which was not logical for the size of his San Jose goat herd and the amount of milk the goats produce. It was also not possible given the farm’s residential location amidst a sea of housing developments.

“Everything was going well until the letter came,” Hulme said of his San Jose farm. This was part of the reason for Hulme’s recent move to 36 acres of ranch land in Hollister, where he hopes to be able to raise the funds to build a dairy and creamery for processing raw milk. On the larger acreage in Hollister, Hulme can raise more goats.

Hulme and three shareholders filed a lawsuit with the Farm-to-Consumer Legal Defense Fund against the CDFA and the County of Santa Clara, claiming that they have a right to consume raw milk produced by their own goats and enter into private herd-share contracts.

“The people who are being injured here are the owners of the goats. The state is essentially denying them access to what they have a right to. There should be nothing illegal about milking a goat and taking its milk home,” Hulme says.

The CDFA’s motion to strike Hulme’s lawsuit was denied and a stay on the case implemented in order to grant the CDFA time to form a working group and study the issue.

“If there is a positive outcome to the working group, in terms of the CDFA voluntarily changing the dairy code to be acceptable to us, then we will dismiss the suit,” Hulme says. His goal is for herd shares to be recognized as legal, practical, and manageable.

“I’m not going to give up on this,” Hulme says. “The dairy laws should not violate our civil rights.”